Our annual cruise to the western Fram Strait has come to an end. We had a tight schedule, but lots of sampling and working around the clock helped us reach our goals:

Photo: Lawrence Hislop / Norwegian Polar Institute

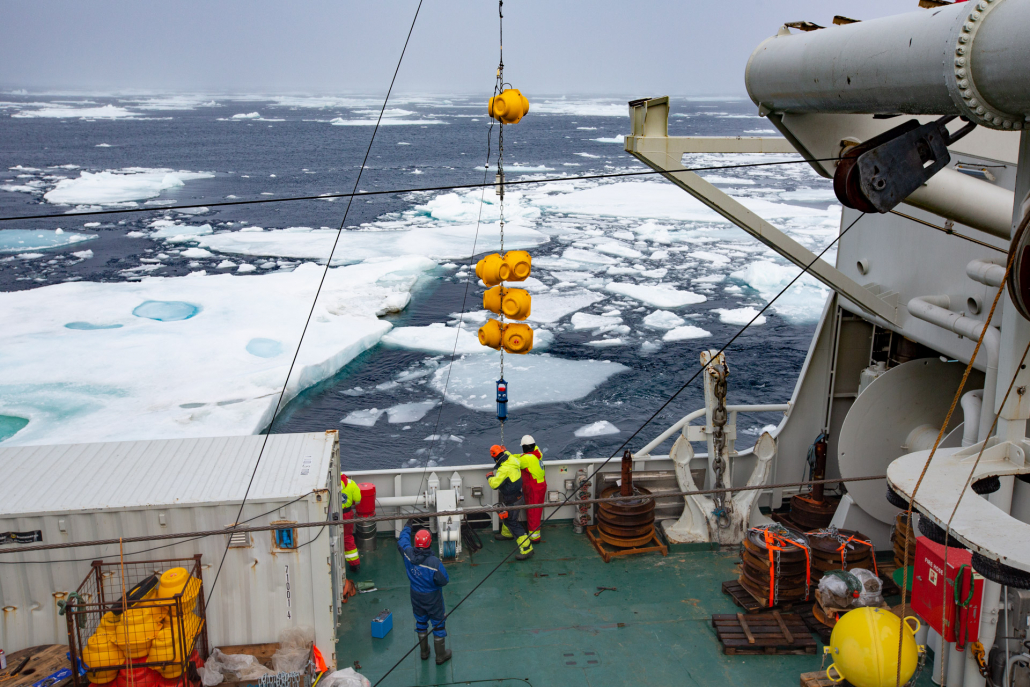

We recovered 6 of our moorings with instruments full of new salinity and temperature measurements of the of the East Greenland Current. Initial results show a lot of warm Atlantic Water on the Greenland shelf the past few months, while the polar water continues to be warmer in summer due to the sea ice decline. Both are important processes that will lead to delayed sea ice formation and likely a thinner sea ice cover this winter. We carried out the yearly hydrographic section across the strait at 78.8° N., where we sampled Arctic waters to understand the effect of climate change on the origin of surface freshwater, nutrient distribution, carbon export and ocean acidification.

Photo: Lawrence Hislop / Norwegian Polar Institute

The Arctic has been unusually warm this summer, with record heatwaves triggering record Greenland Ice sheet melt. This runoff is adding to the freshwater released by melting Arctic sea ice. Because this freshwater influx could affect ocean circulation, it’s important to know where it goes. Does it stay in the narrow Greenland boundary current, or will it reach Atlantic deep water formation regions where it might have a big impact? To find out, we have deployed drifters telling us their position every few hours as they float along. Some also measure temperature and salinity, showing how the freshwater mixes with saltwater over time.

Photo: Lawrence Hislop / Norwegian Polar Institute

Part of this cruise is dedicated to sea ice research in the East Greenland Current. But as in the past few years, we had trouble finding sufficiently large floes to work on again this year. Fog and storms also delayed our work. Luckily, we were able to do an aerial survey with an electromagnetic instrument flown from the helicopter that measures sea ice thickness.

Photo: Lawrence Hislop / Norwegian Polar Institute

Visiting “fast” ice is a crucial part of our research program in the Fram Strait. An extensive area of stationary ice attached to grounded icebergs forms in the shallow waters off northeast Greenland coast every winter. This fast ice has generally been able to survive summers; forming a wide zone of multiyear fast ice more than two- to three-meters thick. Over the past few weeks we have seen this fast ice quickly disintegrate, driven by a combination of regional ocean warming and a northeastern swell that chipped it away piece by piece. When we reached our destination on northeast Greenland shelf at about 14.2°W, 78.5°N, only a small central portion, about 50 km. by 12 km., remained. Here, we took samples of ice cores and seawater at the bottom of the ice for studies on microplastics, which have been found in sea ice. The samples will be analyzed when we return to Tromsø.

Photo: Lawrence Hislop / Norwegian Polar Institute

Bowhead whale. Photo: Lawrence Hislop / Norwegian Polar Institute

Last but not least, the Fram Strait phase of the ICE-whales project is nearly at an end. Weather conditions were largely conducive to searching, but ice conditions in the Greenland coastal polynya system were heavy (vast amounts of glacier ice in particular) and there were no bowheads sighted anywhere on the shelf. We only encountered four bowheads on the entire expedition, all in the mid-strait drift ice. One individual was tagged (sat, limpet) and biopsied. Narwhal were more numerous both coastally and in the drift ice, and we have done novel collections of biopsies from this population, which has never before been sampled. These samples will produce exciting scientific results when compared with the neighboring population to the west on a variety of fronts (genetics, isotopic analyses of diet etc).

Photo: Lawrence Hislop / Norwegian Polar Institute

Photo: Lawrence Hislop / Norwegian Polar Institute