The polar bear does not recognise national borders, and may migrate over large distances through the territories of several countries. The distribution range covers 25 million km2, around the pole, from the North Pole itself in the north to as far south as 47°N on the east coast of Canada. At a time when the species is threatened by climate change, it is therefore entirely natural and essential that the polar bear nations cooperate to implement measures to secure the future of the species.

Concern for the population

Cooperation on the conservation of the world’s polar bears began in 1965, when the Americans were concerned about the large catch in Alaska and Canada in the absence of knowledge of the population status. Representatives of all five nations, Norway, Canada, the United States, Denmark and the Soviet Union, then sat down at the negotiating table. With the help of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the nations negotiated an agreement to protect polar bears which was signed in Oslo in 1973. Under this agreement, the countries agreed that only indigenous hunting would be legal, and that there should be cooperation on research and management to protect polar bear habitats and the ecosystems in which they lived.

The cooperation gradually largely overcame the main problem that existed, which was excessive harvesting in certain areas. And, through the 1980s and 1990s, more knowledge was eventually gained about the conditions and status of the populations.

The group that negotiated the conservation agreement in the period 1965-1973 became established as the IUCN/Polar Bear Specialist Group (PBSG) in 1968. Today, this group consists of the world’s leading polar bear scientists, who now operate as independent scientific advisors to the signatory nations. For three decades, this group was responsible for ensuring compliance with the agreement, and that the cooperation yielded results at a time when the signatories themselves formally remained inactive.

Inuit family in Greenland prepares a polar bear that has been shot/captured. Photo: Jon Aars / Norwegian Polar Institute

New threat from climate change

In 2001, the IPCC issued its third report, which mentioned for the first time the possible effects of future climate change on the ice sheet at the poles. This new threat initially led to polar bears changing their status on the red list from Least-concern to Vulnerable. This in turn led Norway to call a new meeting of the signatories to the 1973 agreement. When the parties gathered in Tromsø in March 2009, it was formally 28 years since they had last met.

Since the meeting in 2009, the parties have held formal meetings every two years. They have met in Canada (Iqaluit), Russia (Moscow), Greenland (Ilullissat), USA (Fairbanks), and most recently in March 2020 in Longyearbyen in Svalbard.

A polar bear census of the Barents Sea population took place over four weeks in autumn 2015. Polar bears are counted and recorded by helicopter and other means. Photo: Jon Aars / Norwegian Polar Institute

Circumpolar action plan

To address the climate threat, international cross-border action is urgently needed. A circumpolar action plan was adopted in Greenland in 2015, with the main vision being “to secure the long-term persistence of polar bears in the wild that represent the genetic, behavioral, life-history and ecological diversity of the species”. The action plan formulates six main objectives, which, in short, are to:

- Minimise threats to polar bears and their habitat.

- Communicate to the public, policy makers, and legislators around the world the importance of mitigating greenhouse gas emissions.

- Ensure the preservation of essential habitat.

- Secure responsible harvest management systems.

- Minimise the number of conflicts between humans and polar bears.

- Ensure that international trade of polar bear products is carried out according to conservation principles.

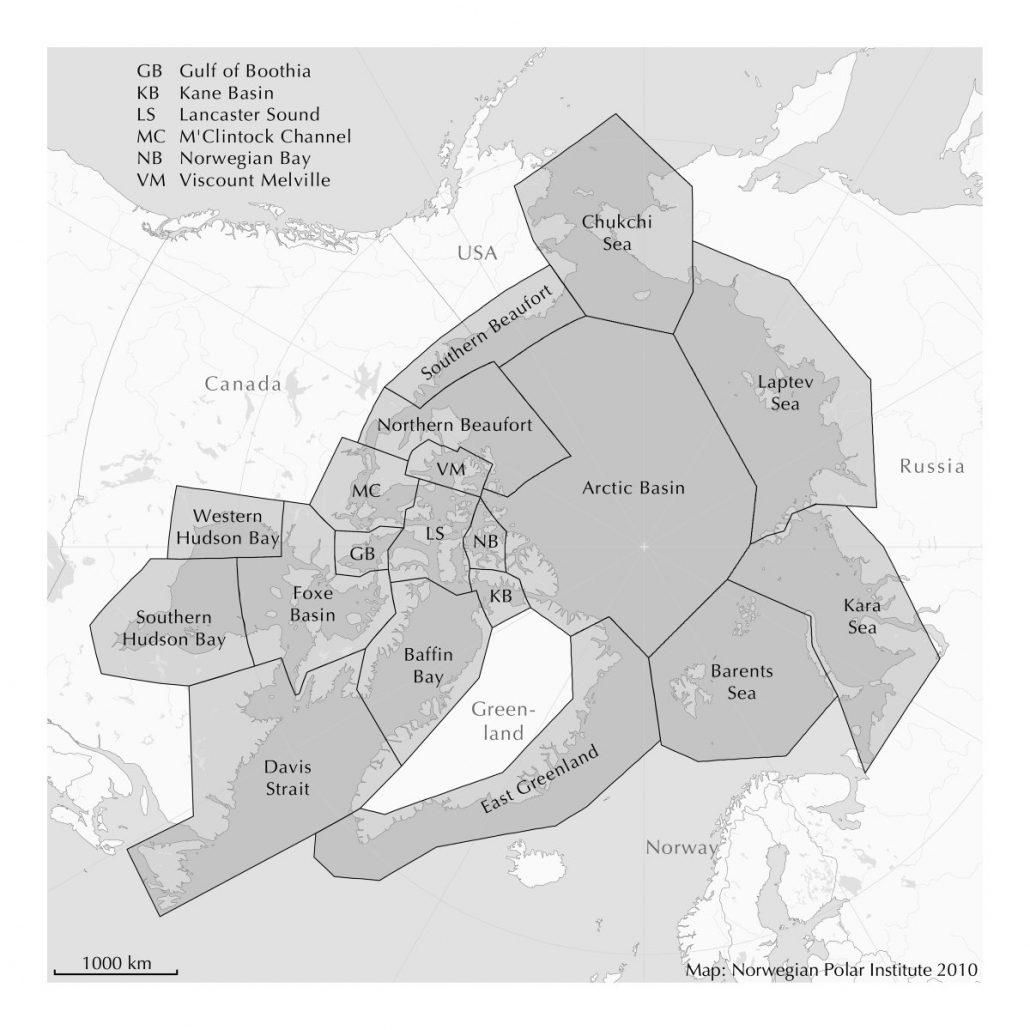

The different polar bear populations Illustration: Norwegian Polar Institute

More challenges

The conservation efforts that the signatories are attempting to implement through their cooperation under the agreement are not without problems. One issue is that international climate policy is not negotiated through an agreement that relates to one species. Both Presidents Bush and Obama made it clear that the United States’ climate policy will be negotiated through the Climate Convention. Not surprisingly, none of the signatories disagree with this decision, which regrettably somewhat dilutes a circumpolar action plan for polar bears.

Global warming will lead to less sea ice, which is a threat for the polar bear population. Photo: Norwegian Polar Institute

Indigenous hunting

Another factor that creates problems between the individual nations is that, in the areas where indigenous hunting takes place, hunting and quota-setting are regulated based on two different knowledge systems, traditional indigenous knowledge and what is known as Western science. Every year, 6-800 polar bears worldwide are officially taken as part of quota-regulated legal indigenous hunts. Over the past two decades, quotas in Canadian sub-populations have largely been set on the basis only of traditional knowledge, against scientific advice. Traditional knowledge is knowledge that is transmitted between generations and which is very largely not quantitative and written down. There are major challenges associated with regulating hunting to sustainable levels in areas where the knowledge base is poor and the populations are in decline.

The future for polar bears

The analyses made for the red-listing of polar bears at a global level outline a future in which their main habitat, the sea ice, is increasingly disappearing and in which they too will disappear from many of their present areas because the ice-free period will be too long. What we can do, therefore, is to ensure that other threats are as minimal as possible and, for this, cross-border cooperation is essential.